Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich - author of "The Tale of Igor's Campaign"

Authors: Begunov Yu.K., Nurutdinov F.G.-Kh.

AT sources that have survived to our time and in the historiography dedicated to the immortal poem about Igor's campaign, nowhere directly refers to either the author or the time of writing.

For more than 200 years that have passed since the publication of the text of the monument by Count A.I. Musin-Pushkin, researchers expressed dozens of different points of view and assumptions about who was the author of the poem and when it was written. So, for example, most researchers believe that "The Tale of Igor's Campaign" was written by someone from the entourage of Prince Igor Svyatoslavich[1].

Among the authors of the poem were the names of Prince Igor himself (N.V. Charlemagne, I.I. Kobzev, V.A. Chivilikhin), the scribe Timofey, the “verbal” singer Mitusa, the boyar Pyotr Borislavich, the Chernigov governor Olstin Oleksich, the “merciful” Svyatoslav III, singer Khodyna, Prince Vladimir Yaroslavich of Galicia and many others.

The time of creation of the "Word" was determined in different ways.[2].So, most historians and philologists rightly believed that the work was genuine and was written shortly after the return of Prince Vladimir Igorevich, the son of the hero of the Lay, from the Polovtsian captivity, in the summer-autumn of 1187: in the text of the monument, the Galician prince Yaroslav Osmomysl is mentioned as alive (d. 1.10.1187).

Seventeen-year-old Prince Vladimir really returned home with his young wife two years after the campaign. Prince Igor with his wife and his second cousin Vladimir Svyatoslavich, Prince of Chernigov, were invited to a fair feast on the occasion of the wedding of Vladimir and Yarsylu at the headquarters of Khan Khondzhak in Alabuga. During the feast, the Bulgarian poet Gabdulla Ulush sang a laudatory song in honor of the newlywed called “Namei Yarsylu Khiri”, i.e. "Song of Maiden Yarsylu"[3]. In it, he glorified the beauty and extraordinary virtues of the newlywed, as well as the power, wealth and glory of her father, inal (judge) Deremely Khondjak. But Prince Igor and his brother Vsevolod got a lot of critical words and even abuse. Both princes are characterized only from the negative side, for example:

And he loved only wealth,

I was ready for him

Commit any crime.

His income was great.

And he captured a lot of prey,

But all these riches were sinking

In the bottomless river of his desires"[4].

At the same time, the Bulgarian singer did not skimp on black paints addressed to Prince Igor: both a dissolute drunkard and an unlucky military leader who lost the battle and escaped from captivity, which was considered a shameful deed. The dishonorable actions of Prince Igor near Alabuga are described only as atrocities.

Prince Igor was deeply indignant. He asked his second cousin Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich, who was sitting next to him at the feast, to write the truth about him and his campaign against the Polovtsians. Euphrosinia Yaroslavna, the wife of Prince Igor, presented the same request to Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich at the same feast. The poet agreed, and a year later, at a feast in Novgorod-Seversky, Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich sang in Russian "The Tale of Igor's Campaign". It was 1188[5]. The reason for the feast was the birth of the first-born son of Yarsylu and Vladimir Igorevich named Takhira, and in Russian - Vsevolod.

The corresponding authentic text is known to us in the transmission of the Bulgar scholar Fargat Nurutdinov (Kazan):

“At the wedding of Khondzhak’s daughter (Konchak) and Uger’s son (Igor Svyatoslavich), Gabdi Ulush performed “Namei Yarsylu Khiri” (“The Word of Maiden Yarsylu”), which Khondzhak really liked and offended Uger. Seeing how Uger was going through, his wife asked Bulymer, the son of Baltavar (Grand Duke of Kyiv Svyatoslav III), write a song celebrating Uger. Bulymer Baltavar (Vladimir Svyatoslavich) could not refuse her and wrote such a song - “Namei Uger sugheshe” (“Word about Igor’s War”), which we have already talked about <...> When Bulymer Uger (Vladimir Igorevich) returned from Dzheremel (Polovtsian steppe ) in Yana Kara Bulgar or Yana Seber (Novgorod-Seversky) with his wife Yarsylu and son Takhir (Vsevolod), a new wedding feast was arranged for them, at which Bulymer Baltavar performed "Namei Uger sugeshe" "[6].

Let's say a few words about the origin of the quoted text. The authentic Turkic text, written on parchment in Arabic script, has not survived to this day. Bulgar oral tradition IX—XX centuries they associate its storage and correspondence (copying) with the followers of the Bulgar educator, political figure and philosopher Sardar Gainan Vaisov (1878-1918), who headed the party of the Volga Bulgars - Muslims "Firkan Nadzhiya". In the cultural and educational center of this party, ancient Bulgarian chronicles, poems and cult books written in Bulgaro-Arabic letters in the Turki language were kept and passed from father to son for a long time.[7]. In the end XIX—XX centuries the keepers of these manuscripts were first the Kazan community of the Bulgar-Vaisians, and then the Nigmatullin family, exiled at the end XIX in. by the tsarist government from Kazan to Kazakhstan, in the city of Kyzylyar (Petropavlovsk). There were until 1939 the originals of several Bulgarian chronicles of the Middle Ages, until a misfortune happened: the local NKVD found them and destroyed them. Only translations and retellings in Russian of some of these unique materials remained, the custodian of which from 1966 to the present is the Kazan researcher F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov[8]. He is the nephew of Ibragim Nigmatullin (1916-1941).

According to the family tradition of the Nigmatullins - Nurutdinovs, in the 1920s. a certain Saifullin, from the Vaisovites, organized the Peter and Paul translation of the Bulgarian chronicles into Russian. They were translated by two Russian teachers, as well as seven Bulgar-Vaisovites. Here are their names, preserved thanks to the Nurutdinov family giving: Akhmad Gadelshin, Khadi Valiev, Nabi Gazizov, Khabibrahman Miftakhutdinov from Agryz, Masgut Shafikov from Orenburg, Mohammet-Karim Nigmatullin and two teachers of the Russian language of the Petropavlovsk gymnasium Sadovsky and Ovchinnikov. In the 1930s Ibragim Nigmatullin copied the translations made into his notebooks. As it turned out, the translators translated the texts of five ancient Bulgarian works, namely: the poem by Mikail Bashtu "Shan kyzy dastans", the collection of the Volga-Bulgarian chronicles of Bakhshi Iman "Dzhagfar tarihi", the legends of Vasyl Kush "Baradj dastans", the collection of Karachay-Bulgarian chronicles of Daish additions. Among these materials, the Chronicle of Nariman, or "Nariman Tarihi", which contains the history of Bulgar and Khazaria, attracts attention. Based on the surviving records of the Nigmatullin family, Nurutdinov managed to establish that Nariman was a Bulgar biy, i.e. prince, who began to write his chronicle in the Turki, citing quotations from the Koran in XVin., and continued in XVI in.; finished writing it in the third quarter XVI in. sons of Nariman. Judging by the surviving Russian translation of the text, this original was a valuable source on the history of the Volga Bulgaria, Khazaria and Rus', who used a number of texts that have not survived: "Kashan tarihy", a chronicler XI in. Bish-Arab, son of Gazi-Yusuf, grandson of King Talib, "History of the Khazars" by an unknown author, "Karachay History" by Daish Karachay. "Nariman tarihi" differed markedly from "Djagfar tarihi": this is how many information was preserved in it, incl. and about the author of The Tale of Igor's Campaign.

Turning to two newly found sources - Gabdi Ulush's poem "Namei Yarsylu Khiri" and "Nariman Tarihi" - allows us to understand the creative history of "The Tale of Igor's Campaign" and clarify the name of the author and the date of occurrence.

As his main source, which Prince Vladimir chose to follow, was the poem of Elaur Ryshtavly "Bulyar sugeshe yry", i.e. story "About the Bulyar war". The very beginning of this poem testifies to the similarity of the two texts.

Compare:

| "Bulyar sugesh yry"21

“Should we not sing, brothers, In the words of the Bulgarian language One military deed - The war of Bulymer Bat-Aslaply? Or should we sing The whole Bulyar war, In which, together with Bulymer Did Syp-Bulat Balynsky fight? And isn't it better for us to sing All the heroes of this war The way Boyan did it, The Nightingale of Old Time? Boyan Kuban when he wanted Sing someone He said: “Oh, Tangra, There is no greater greatness in the world! Give me the ability Spread Uroy Along Boy-Terek And according to the Bulgar Tree! Let me, incompetent, run like a wolf Along the Turdzhanskaya trail Through the fields up the mountain. Give me earthly Rise like a blue eagle Under the clouds Heavenly Wisdom! And then Boyan, the grandson of Vylyakh, Remembering the old days And asked to listen Ancient Alankhai and Vylyankhai About Samara and Idel, About Ilat and Suldan, About Djurash and Dzhurdan, And about Paul Bulgarsky. Remembering the times The first human strife He sent ten falcons To a flock of swans. The swan that Falcons overtook, started to sing About the old Alps and heroes. |

"The Tale of Igor's Campaign"

“Is it not wrong for us, brethren, start with old words difficult stories about Igorev's pulka Igor Sviatoslavich? The beginning of this song according to the epics of this time, and not according to Boyan's intention. Boyan bo grand, if anyone wants to create a song, then the thought will spread on the tree, with a 7 swarm on the ground, Shizy eagle under the clouds. Remember more, speech, the first time of strife. Then push ten falcons to a flock of swans: which dotecha, that front song of the belt old Yaroslav, brave Mstislav, ie Zaza Rededu before kasogsky pulky, red Romanov Svyatoslavlich. Boyan, brethren, is not a falcon on a herd of swans more densely, not your own v7shchia live strings vskadash, they themselves are the prince of glory rohotahu"[10]. |

Fargat Nurutdinov was the first to confidently name the author of the great poem in 1993: Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich[11].

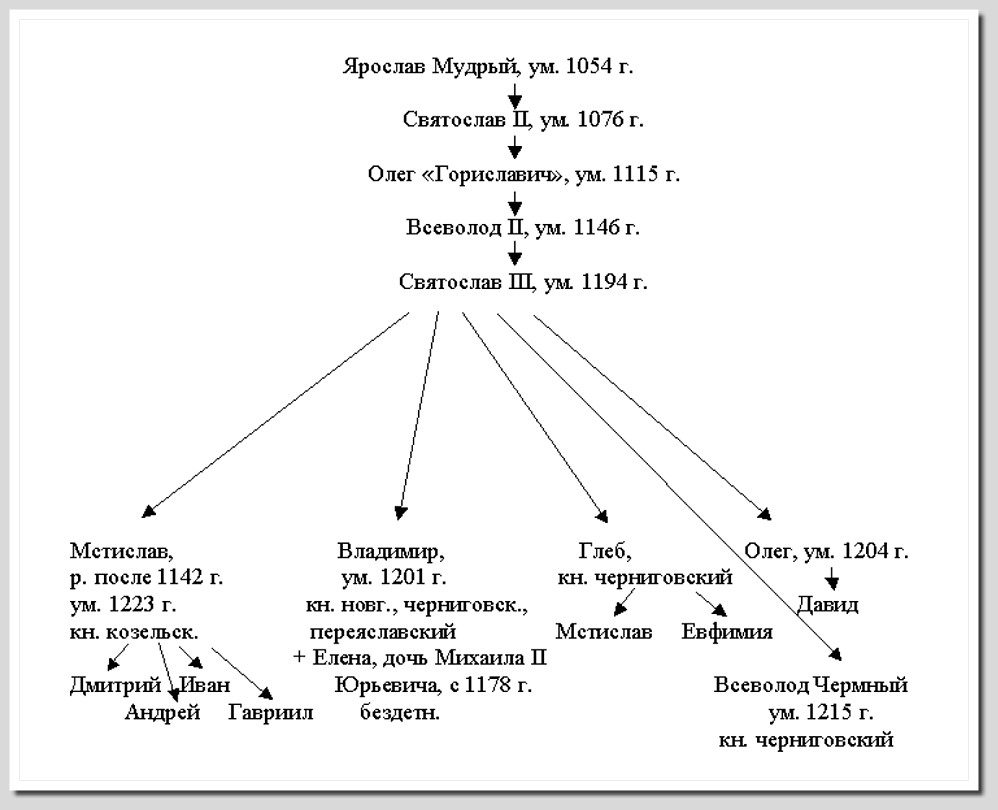

Here is the genealogy of the author of The Tale of Igor's Campaign.

The author of the work is a typical prince Rurikovich of his time. He was the second son of the Grand Duke of Kyiv Svyatoslav III Vsevolodovich (c. 1116-1194), grandson of the Grand Duke of Kyiv Vsevolod II Olgovich, great-grandson of Oleg "Gorislavich", Prince of Chernigov. His mother was Princess Maria Vasilkovna, daughter of Prince Vasilko Rogvolodovich of Polotsk, a descendant of the famous Prince Vseslav Charodey. Prince Vladimir was born after 1142 in Novgorod-Seversky during the reign of his father there and received the usual princely education and upbringing. He got acquainted with the princely and monastic libraries, learned about the work of storytellers of Kievan Rus IV—VI centuries: Boyan the Prophet, son of Prince God, Malota, Kyiv, Prasten the Prophet. This acquaintance affected the entire figurative and stylistic system of the “Word”, rich in metaphors, epithets, comparisons, reminiscences of paganism, where Boyan is called the grandson of Veles, the Russians are the grandsons of Dazhbozh, the winds are mentioned - the grandchildren of Stribog, Karna and Zhlya - the goddess of sorrow, the maiden Resentment, Div calling at the top of a tree, etc. It is no coincidence that the author conveyed to us two ancient Ukrainian names of the trident - Troyan and Southern Rus' as "the land of Troyan"[12]. In his poem, Prince Vladimir did not forget to condemn Vladimir Monomakh, who caused a lot of trouble to the Polovtsy of Deremela and reminded that all the Chernigov nobility, whom he knew firsthand (Vladimir was a specific Chernigov prince), consisted largely of representatives of the noble Bulgar families Masguts, Tatrans, Shelbirov (Chelbirov?), Topchyakov (Tubdzhakov), Revugov (Arbugintsev), Olberov (Elbirov), etc. He also knew the Bulgar guns - sherejirs, which shot with fire. End XII in. was the time when the Bulgar nomads of the Kara-Saklany masses adopted Christianity and switched to the Russian service, which led to the pacification of the Polovtsians and the Russification of part of the Polovtsian steppe. For this, the princes of Kyiv, Chernigov, Pereyaslav and Novgorod-Seversky gave the Polovtsian nobility lands and Tarkhanate, married Polovtsian women; From the Christian Bulgars, the Cossacks of the Kara-Saklan steppes were also formed, which carried out border service with detachments of the Chirkes.

"The Tale of Igor's Campaign" was distributed among the princely milieu and did not receive wide popular distribution, since it was addressed directly to the Russian princes in order to force them to abandon civil strife just on the eve of the terrible enemy invasion. The poetic manner of the author of The Lay is close to the poetic manner of Bojan Busovich, a singer IV century, the author of the famous "Hymn"[13]. At the beginning, Prince Vladimir seems to refuse to follow the manner of Boyan, who often used epithets, metaphors, comparisons, anaphoras, epiphoras and other poetic tropes and figures, and seems to want to write according to "epics of this time."

"Come on, brotherie, tell this story, - the author begins his work, - from old Vladimer to the current Igor, even if I wear out my mind with my strength and sharpen my hearts with courage, having filled with the military spirit, bring your brave cry to the Polovtsian land for the Russian land "[14].

However, in fact, Prince Vladimir returned to Boyan's old poetic style in the spirit of combining "glory" and "weeping", weaving together both halves of poetic time: both past and present. As a result, he created a wide epic canvas of military events of the era of confrontation between Rus' and the Steppe, written with unusual precision and conciseness and with great artistic expressiveness under the sign of eternity!

In ancient Russian literature, two more works similar to the Tale of Igor's Campaign have been preserved. These are “Praise to the Grand Duke Roman” from the Galicia-Volyn chronicle under 1201 and “The Word about the destruction of the Russian land”, the middle XIII in. In them, the authors set themselves the same tasks: the glorification of the Russian land and its powerful defenders - the Grand Dukes.

The entire “Word”, in which there is no excessive verbal material, is filled with incredible dynamism: everything lives, moves, sounds, acts in it. This is a feature of poetic skill. It is present in the very structure of the Lay, created by the great scribe, such as Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich of Chernigov. Under the author's pen, an insignificant episode of the Russian-Polovtsian wars turns into a key event of all-Russian significance: after all, the author calls on the Russian princes to avenge the defeat of Prince Igor, "buoy Svyatoslavlich", to intercede for the Russian land! Among such intercessors, he sees the Vladimir-Suzdal prince Vsevolod III The Big Nest, whom the author of the poem knew well personally and took part in his campaign against the Volga Bulgars in 1183:

Do not think of you flying from afar

Take away the gold of the table to observe?

You can scatter the oars on the Volga,

And Don pour out the helmets!

Even if you were

That would be chaga by foot,

And cut the bones.

You can also dry

Shoot the shereshirs alive,

Deleted sons of GlÚbov»[15].

He also considers Svyatoslav to be the intercessor of Prince Igor. III, who actually did not enjoy such authority in Rus'. The author of the Lay contrasts the power and valor of the Grand Duke of Kyiv with the infirmity of Prince Igor, who, with his foolish actions, destroyed what the formidable Svyatoslav had created:

Igor and Vsevolod -

I'm already lying ubudista which,

That byashe their father slept -

Svyatoslav the terrible great Kiev thunderstorm:

Byashet ruffled with his strong plys

and haraluzhnym swords;

step on the Polovtsian land,

trampling chlami and yarugi,

stir up rivers and lakes,

dry up streams and swamps.

And the rotten Kobyak from the bow of the sea

from the iron great plows of the Polovtsian

like a whirlwind, vytorzhe:

and grazing Kobyak in the city of Kiev,

in Gridnets Sviatoslavl.

Tu Germans and Venedians,

to Greece and Morava

sing the glory of Svyatoslav,

cabins of Prince Igor,

already immerse the fat in the bottom of the Kayala Polovtsian rivers,

pour Russian gold.

Tu Igor the prince came out of the gold,

and in sÚdlo koshchievo.

Unysha was taken away by hail,

and the fun is lower"[16].

The same valiant intercessor seems to the author to be Prince Yaroslav Osmomysl of Galicia, who was the father-in-law of Prince Igor and was still alive until 10/1/1187; This means that this text was written before that time. Here's what it says:

Sit high

on your gold plated table,

propped up the Ugrian mountains

with your yellow plaki,

stepping in the gates of the Danube,

sword burdens through the clouds,

courts as far as the Danube.

Your thunderstorms flow across the lands,

open the gates to Kyiv,

shoot off the gold of the table

salatani for the lands.

Shoot, mister, Konchak,

filthy cat,

for the Russian land

for Igor's wounds,

buoy Svyatoslavich![17]»

Before us is a hyperbolic, highly exaggerated characterization of the Western Russian Galician Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich, who allegedly possessed "eight senses", minds, and constantly suffered from his boyars. Here he is turned into a giant hero, sitting high on his gold-forged throne, propping up the Carpathians with his iron regiments and blocking the way along the Danube. Of course, all this did not happen, but the author of the Lay needed this exaggeration. He, as it were, rose above reality and designed his ideal world, in which everything should be beautiful. Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich did his best to idealize and glorify the personality of Prince Igor. The author of the Lay understands well the reasons that led Kievan Rus as a state to decline, and writes about it this way:

already covered the strength of the desert.

Resentment arose in the forces of Dazhbozh's grandson,

entered the land of Troyan with two,

fluttered swan wings

on the blue sea near the Don

splashing, lose fat times.

The strife of the prince on a filthy death,

recosta bo take brother:

"This is mine, and that is mine."

And swearing princes about small things

"this great" mlviti,

and forge sedition on your own,

And the trash from all countries comes with victories

to the Russian land![18].

Against the background of these troubles, the behavior of Prince Igor was not impeccable, but he wanted to honestly try his luck as a knight and “break the end of the Polovtsian field with a spear” in order to “drink the Don with a helmet”, since

rather full of being "[19].

In other words: “We sing a song to the madness of the brave, the madness of the brave is the meaning of life!” (Maksim Gorky). And once again, the brave lost, and already “longing has spread over the Russian land”, “... and the abominations themselves, with victories coming to the Russian land, tribute to the earth from the court”[20]. This is the main invective to the princes for their political adventurism and recklessness, which sounds quite convincing from the lips of the Chernigov prince, who knows firsthand how to properly manage the Russian land in the interests of the whole people. He emphasizes the disobedience of princes Igor and Vsevolod in relation to their main overlord - "father" SvyatoslavIII and condemns them for it. The author calls for feudal fidelity, which was associated with the observance of feudal principles in the name of the interests of the entire Russian land, so that it does not die, so that the candle of the Russian Family does not go out. The unity of the Russian land and the well-being of all the Russians were coupled to him with the idea of \u200b\u200bstrong princely power, which would be exercised by the formidable Grand Duke of Kyiv. A strong grand princely power was just beginning to emerge, and not in the south, but in the north-east of Rus', as an idea of autocracy, purely monarchical, to which Rus' XII in. not yet lived, and she still had to live up to it under the Moscow tsars. According to the genre, "The Word" is one of the so-called. "chansons de geste”, i.e. "songs of exploits" like the old French "Song of Roland"[21]. In genre and stylistic terms, the “Word” is close to the monuments of Greek-Slavic solemn eloquence, or epideictics, in which the ancient Greeks glorified their gods and heroes, as noted by I.P. Eremin. Before us is a monument of secular artistic political eloquence, i.e. topical, journalistic about the unsuccessful campaign of Prince Igor of Novgorod-Seversky against the Polovtsy in 1185. The time of the creation of the work by I.P. Eremin guesses exactly: 1187 - 1188, in the "unhappy year", when the Polovtsy everywhere attacked the Russian land, inspired by the defeat of Prince Igor. The author, Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich, names thirteen Russian princes of that time by name: Svyatoslav III and his brother Yaroslav Chernigovsky, Rurik Rostislavich and his brother Davyd Smolensky, Yaroslav Vladimirovich "Osmosmysl" Galitsky, Roman Mstislavich Volynsky, sons of Yaroslav Izyaslavich Lutsky - Mstislav, Ingvar and Vsevolod, grandson of Vseslav Charodey Yaroslav, Vsevolod III. This gives the Lay a sensational topicality: after all, the author, while paying tribute to their valor and courage and readiness to always come to the aid of the Russian land, nevertheless reproaches all of them for inaction and indifference to the Russian land, to the wounds of the valiant Igor, that all taken together makes you regret the past: “Oh, the groans of the Russian land, who remembered the first year and the right of the princes!”. The main appeal of the topical "Word" is the immediate protection of the Russian land from the Polovtsians. In this our poem is consonant with the Kyiv Chronicle XII in.

“The Kyiv Chronicle,” notes I.P. Eremin, - testifies that the princes, gathering on a dream or sent as ambassadors, spoke more than once about the need to "observe the Russian land and be all for one brother" (p. 257 edition of the annals in the PSRL. T.2. - Yu.B.) , more than once expressed the desire to “suffer” for the Russian land (p. 257), “guard” the Russian land (p. 258), “do not destroy the Russian lands” (p. 297), quit the internecine struggle “Russians dividing the land and dividing the peasants "(p. 266). Sometimes these formulas covered up very prosaic plans and calculations, but there were times when they reflected a genuine patriotic enthusiasm, expressed the real readiness of the princes to fight for these lofty principles. And in these cases, the speeches of the princes, judging by the annals where they are reproduced, more than once rose to a great ideological height and breathed ardor and the power of persuasion. Such, for example, is the speech with which in 1152 Prince Izyaslav Mstislavich addressed his retinue, preparing at Przemysl for a battle with Vladimir Galitsky, who had recently sacked a number of Russian cities: “Brothers and retinue! God always Russian land and Russian sons in dishonor did not put there; in all places they took their honor. Now, brothers, all are jealous of this, in these lands and in front of foreign languages, God give them their honor to take ”(p. 310). Or the speech that Mstislav Izyaslavich delivered in the princely dream in 1170, preparing a campaign against the Polovtsians: “Brothers! Take pity on the Russian land and on your father and grandfather, and carry the peasants for every summer with their own, and with us the company is charging, always stepping over; and already we are taking away the Greek way, both Salt and Zalozny. And it was expedient, brothers, to help God and pray to the Holy Mother of God, to search for our fathers and grandfathers for their ways and their honor ”(p. 368).

Life itself, local Kyiv reality XII in. prompted the author of the Lay not only the content of his work, but to some extent, as we see, also its artistic form. This form turned out to be the “Word”, within which the author raised this living practice of oral speech of non-literary origin, well known to him, to the height of a literary work, armed with all the powerful apparatus of artistic influence on the reader, developed in his time by the solemn eloquence of Kievan Rus.[22].

The composition of the Lay is divided into five parts: 1) a folk-poetic and rhetorical introduction, the main part, which, in turn, is divided into three sections; 2) about the campaign of Prince Igor; 3) about Russian princes; 4) about the flight of Prince Igor from captivity; 5) conclusion, which tells about the return of Prince Igor home, his meeting and praise of princes Igor, Vsevolod and Vladimir, as well as the squad[23].

The main part is full of literary episodes, for example, the prophetic dream of Svyatoslav III, his “golden word” with mixed tears, an appeal to the Russian princes, a description of the sorrow of the European peoples who learned about the defeat of Prince Igor, the cry of Yaroslavna, conjuring the forces of nature to help her husband, a fictional conversation between the khans Gzak and Konchak, etc.

Yaroslavna's lament is partly reminiscent of the lament of Yarsylu, Konchak's daughter, from Gabdulla Ulush's poem Namei Yarsylu Khiri. Here are these texts:

| "Lament for Yarsylu"[24].

“Dawn came or not? And does the dawn shine with gold? Early in the morning I cry out loud: Are there people more unhappy than me? I have a fiancé Son of Mar Suren, But he can't Come to me. Mar, radiant Mar, You are loved by all With your light, warmth, And its beauty! Why are you, Abalan, Don't you want to look at me Your bride: After all, your son is my fiancé! 'Cause I'm so beautiful Nothing offended you. Always praised and honored you And I'll be your good daughter-in-law! Rather drive away the darkness and the cold, Rather, look at me from Heaven - And send Suren to me On your glittering ship! Oh, Tunburi, glorious Alp! You broke through the Divovy Stones, So that Idel can Flow through Bulgarskaya earth! You are so many eras Carefully rocked on the waves And carried with its currents Bulgar ships! So break the ice on the river And bring me more The ship of my dear Suren, So that I don't cry for him! Oh, Gil, Gil, - Ereren! Why, light-winged Gil, You don't blow much On the sails of Suren's ship? 'Cause you can Soar high into the sky Whole swarms of clouds And cause strong hurricanes! So blow harder On the sails of Suren's ship, To my sadness Rather scattered around the world! Where are you, my fiancé, Dear Suren Bahadir, Your Yarsylu is waiting for you: Come here soon, Lele! I'm burning with impatience: I don't know if I can wait? Send me soon Your golden arrow! If I don't get it now I'm dying of impatience! Load up your bow And send me an arrow!” |

"Lament of Yaroslavna"

"On the Danube Yaroslavny I hear zegzitseyu is unknown early kychet: “I will fly, I will speak, I will fly along the Dunaev, I will wet the bebryan sleeve in KayalÚ rÚtsÜ, morning to the prince of his bloody wounds On the cruelty of his body. Yaroslavna cries earlyin Putivl on the visor, arcuchi: “Oh, wind, wind! What, sir, are you forcibly weighing? Why are Khinov's arrows moaning on my own wings in my own way howl? Is there a mountain under the clouds, lolling ships on the blue sea? What, lord, is my joy feather grass developed? Yaroslavna is crying early Putivlyu city on the fence, arcuchi: “About the Dnieper Slovutitsa! You have broken through the stone mountains through the Polovtsian land. You cherished you on s7bÚ Svyatoslav nasas To the cry of Kobyakov. Raise, lord, my fret kj min7, but would not send tears to him at sea early. Yaroslavna is crying early in Putivl at the visor of the Arkucha: “Light and cracked sun! Be warm and red to everyone: Why, sir, open space hot your beam how about? In the waterless field I crave their rays conjugation, tight im thulia zatche?[25]. |

Between these two texts of laments there are some coincidences in motives. So, for example, in a spell of the forces of nature, say, the wind, which blows slightly on the sails of the ship of the beloved, in one case, the groom Suren, and in the other, her husband Igor. He, the powerful Alp spirit, cherishes the ship of the groom or husband on the river or on the blue sea. In one case, the Alp Tunburi, and in the other, the Dnieper Slovutich breaks through the stone mountains, or Divovy stones, i.e. Ural, in order to Idel, i.e. The Volga, was able to flow through the Bulgar land, in one case, or through the Polovtsian land, in another case, which coincides here in a geographical sense. According to the spell, the water element should cherish, i.e. save the ship or boat of your beloved, so that Yarsylu or Yaroslavna do not cry for him in vain, do not send their tears over the blue sea. In both cases, the beloved sends her prayers to the bright Alp Mar, or the bright and crackling Sun, famous for light and warmth, then to drive away darkness and cold and return the beloved home on a sparkling ship or boat. The spell does not go unanswered. It is heard, and the groom or husband returns to his beloved. In a successful outcome, the meaning of the spell is both Bulgarian and Russian. And so it is optimistic.

The poetics of "The Tale of Igor's Campaign" is very rich, original and original, because this work belongs to the pen of an outstanding master who combined three traditions: 1) oral folk art dating back to pagan times, 2) the Christian culture of the historical story of the war, and also 3 ) rhetorical culture of secular oratorical prose with its methods of organized artistic speech. The modern researcher B.L. Gasparov characterizes the features of our heroic poem in this way: “First of all, it is necessary to note in this regard the unusually complex and sophisticated nature of the poetics of the “Word”: the esoteric play with leitmotifs, the mosaic nature of the genre and stylistic fabric, the multi-level symbolism, the ambiguity of the images and expressions used , difficulty and obscurity of presentation, resulting from a unique combination of multidirectional factors. These features of poetics are to a greater or lesser extent characteristic of otherwise diverse works of the late Middle Ages, such as the German-Scandinavian epic, the lyrics of the troubadours, Dante Alighieri's "Divine Comedy" <...> The Word has the greatest number of points of contact with the heroic epic of the end XI - start XIII centuries: "Song of Roland", "Song of my Sid", "The Knight in the Panther's Skin" by Shota Rustaveli. All these works have an extended epic form, which freely includes digressions of a didactic or lyrical nature. The narrative is based on real events and deeds of earthly heroes, although they sometimes acquire an exaggerated coloring. All works of this kind are characterized by a complex of features, which D.S. Likhachev defined as “the style of monumental historicism”, the presence of “panoramic vision”, the ability to look at events in a generalized way, as if from a great height, a combination of monumentality and dynamism, manifested in the conjugation of times and distances, in the rapid movement through epochs and spaces, “fullness of style ”, which is expressed in enumerations. However, along with these important similarities, no less significant differences are found that do not allow unconditionally classifying The Lay as a heroic epic genre. On the one hand, the "Word" is distinguished by a much greater approximation to reality, concretization and detailing of descriptions. The work is dedicated not to the distant and half-dissolved past in a legendary haze, but to the events of the present or the recent past, preserving complete discreteness, distinct local and temporal localization in the fullness of relevant details, realities and allusions. In this regard, the "Word" is closer to the Icelandic sagas. XIII century, with their orientation to the events of the recent past and to the saturation of the narrative with specific details, organized in accordance with the principles of the poetics of the genre"[26].

Numerous appeals to ancient Russian Vedic poetry, the founder of which is Boyan, “Velesov’s granddaughter,” have not a mythological, but a poetic meaning. They are not so much rhetorical embellishments as they show the connection between the poetic worldview of the author and the symbols and images of pre-Christian Rus'.[27]. This is explained by the fact that the author of the Lay, Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich of Chernigov, was an outstanding writer of his time, who mastered the entire palette of writing skills. Thus, the author often turns to the revival of the forces of nature, which, as it were, participate in the development of the action and empathize with the characters. For example, Yaroslavna conjures the forces of nature to help her husband. The Seversky Donets River helps Prince Igor escape from captivity. The trees bend to the ground, the grasses droop with pity. The old Bulgarian Alp-spirit Div is not forgotten, making ominous sounds from the tops of the trees. And the virgin Resentment (the mother of the Antichrist, according to I. Klein) fluttered her wings, empathizing with the tragic events. The spirits of Karn and Zhlya galloped across the Russian land, fanning the fire of misfortune in a fiery horn. The importance of water in the development of action in the poem is great. The life of the water element (rivers, streams, lakes and reservoirs) is put in close connection with the life of the Russians. The author refers to the rivers as living beings that can be either hostile to a person (Kayala, Nemiga, Stugna), or merciful (Donets, Dnieper-Slovutich). Images of pagan gods are given in the system of natural phenomena. The sun, water, trees, grass, wind, clouds - all of them are animated and connected with human destinies, favor people, one way or another are woven into the dynamics of events, speeding up or slowing down the course of action. The Lay uses the cult of the Family and the Earth, which is very important in ancient Russian paganism and not indifferent to Christianity, since the Most Holy Theotokos became the patroness of the Russian land, and concern for the Russian Family runs like a red thread through all ancient Russian literature. After all, the land was given to a person to arrange his life and ensure the continuation of the family, and the princes, according to the Russian chronicles, must take care of the land, the family and the Russians, their subjects. In the "Word" we observe the further development of the solar myth, according to which the light of the sun is given to man by God, since light is life, this is the Christian Orthodox faith, and paganism is filth, darkness. Therefore, Prince Igor is light-light, and his opponents - the Polovtsy - are filthy, dark. The essence of the worldview of the author of the Lay is the struggle of light with darkness, Rus' with the Steppe. Therefore, God brings Prince Igor out of the dark Polovtsian steppe and shows him the way to the light-bright Russian land. And all the forces of nature help Prince Igor to escape from captivity, because this is an escape from darkness into light. In the end, Prince Igor returns home safely and the first thing he does is visit the Church of the Most Holy Theotokos Pirogoscha in Kyiv and thank Her for bringing him out of captivity. There is much more Christianity in the "Word" than in the Byzantine epic "Digenis Akritus", the French "Song of Roland", the German "Nibelungs", because the author of the poem was an exemplary Christian and a valiant warrior.

One should, perhaps, agree with the folklorist V.F. Miller that the author of the Lay is “a Christian who does not recognize pagan gods and who mentioned them with the same intention as the poets XVIII-th century they talked about Apollo, Diana, Parnassus, Pegasus, etc. ”[28].

As a result, the pagan myth, which has completely lost its religious suggestiveness in literature, becomes an inexhaustible source of poetic inspiration and aesthetic pleasure for the intelligent public.

Created in the late 1180s. in the wake of events by a relative of Prince Igor and by his personal order, the ingenious "Word" amazed contemporaries with a harmonious combination of content and form, a perfect combination of beauty and wisdom, nobility and courage, kindness and friendship. The researchers called the "Word" a heroic prologue to Russian literature, which had yet to reach unprecedented prosperity and great achievements. Academician B.A. Rybakov wrote: “The poet rose above both space and time. He also raised his listeners to this height and, as it were, revealed to them a map of Europe from Venice to Veliky Novgorod, from Germany to the Polovtsian field, from Byzantium to the Volga and the North Caucasus <…> The abundance of colorful images, juicy characteristics, folk sayings, symbols are not obscured in the poem the main patriotic idea, its task to rally all the forces of Rus'. No wonder art historians have found in the old Russian architecture XII in. white-stone likeness of the "Word". This is the Dmitrovsky Cathedral in Vladimir, all covered with carved patterns, hundreds of figures of horsemen, centaurs, lions, fantastic birds, bizarre stone foliage. There are so many patterns that the entire upper half of the building is completely covered with these countless reliefs like a golden cloak. But this generous abundance of decor does not obscure the whole: as soon as we step aside, we will not see the sum of ornamented stones, but a slender, musically harmonious whole.

Such is the "Lay about Igor's Campaign".

It is not surprising that the Russian people, who lived among the bloody and senseless princely strife and wars, immediately fell in love with the great "Tale of Igor's Campaign"[29].

The correctness of K. Marx is fully confirmed, who in a well-known letter of 1856 to F. Engels correctly assessed both the nature and meaning of the poem: princes to unity just before the invasion of the Mongols "[30].

The reward for the author of The Lay was the eternal life of his work. Composer A.P. Borodin wrote the heroic opera Prince Igor (1887), based on the plot of The Lay, by B.I. Tishchenko - ballet "Yaroslavna" (1974).

The text of the Lay was translated into many languages of the peoples of the world; many paintings and works of fine art have been created on the theme of "Words"[31]. Now "The Word" is considered by almost all the masterpiece of Russian literature. XII in [32].

Application.

Fragments of the Bulgar text of the poem by Gabdulla Ulush to the Turks, preserved in the archive of F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov and transmitted in Cyrillic by the employees of Saifullin's group.

| Text

25. Ai, tan miken, tan miken, Tannin jarymlary bar miken? Tannar atkan chakta kychkyryp elim, Minnen yazulyrak barmican? 59. Kara bolyt kile le, Yauly kigse yakhshi idea. Mine alyrga kileler, Almy kitse yakhshi ide. 62. Buran gyna Buran Burymy, Lachyn koshlaren yerak kumiymy? Barygyz, Duslarim, Bagygyz, Khalja koshlaren kilep tulmiima? 65. Susadym, duslarim, sular kaida? Dingez sularynda yuk fiida! Bezge inde mallar kaida; Bashlar sau bulsa, shul fida! 67. Nichek kildegez sez bezga, Batmaencha dingezge? Kaderle kunak sez bezga, Nor hormet kuynym sezge? 143. Echesem kile, echmimen, Echem zhanym koigenge. Zhyrlamyym zhyrlar belgenge, Zhyrlym season soygenge! |

Translation

25. Has dawn come or not? And does the dawn shine with gold? Early in the morning I cry out loud: Are there people more unhappy than me? 59. A black cloud is approaching: It will be nice if it doesn't rain. They're coming to pick me up. It would be nice if they didn't take it. 62. The blizzard winds and swirls, Does it carry the falcons away? Come, friends, take a look Has a flock of Khaljans arrived? 65. I'm thirsty, friends. But where is the water? There is no sense in the waters of the sea! We have nowhere to take wealth. If we don't lose our heads, and That's okay! 67. How did you get to us, Without drowning in the sea? You are our dear guests! What to feed you? 143. I want to drink - but I will not: I drink only from great thirst. I will sing, but not because I can, And because I love you! |

Our comment

About a hundred Bulgarian words for the Turkic poem XII in. preserved by the Bulgarian translators who worked in Petropavlovsk in the 1920s and 1930s under the guidance of Saifullin. I.M.-K. copied them into his notebook. Nigmatullin, and then on the leaves - F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov. If we take into account that "Lex Kumanica", XIII century, preserved only 10 Polovtsian (Bulgarian) words, then we have living fragments of a valuable ancient heritage. They need to be studied.