PAfter the capture of Kazan by Ivan the Terrible and the annexation of the Kazan Khanate to Rus', it included a territory inhabited by Muslim peoples - Tatars, Bashkirs - with their diverse culture. The Orthodox civilization with its foundations absorbed another, the Muslim one, with its faith, way of life, culture and history. In the depths of both civilizations, their own history was created - the history of not only the peoples included in this civilization, but also other peoples of Eastern Europe. The Tale of Bygone Years, chronicles and legends were written in Rus'. Their authors used in compiling them, in addition to their own data, Byzantine sources. And in the bowels of the Kazan Khanate and long before its formation in the Great Bulgars on the Volga, their own history was written, fed by Bulgar and Khazar sources.

However, the fate of these written sources - Russian and Bulgarian - was different. Russian chronicles formed the basis of our national historiography. And the Bulgarian chronicles written in the Bulgarian Türki in the Arabic script hid in the Bulgaro-Tatar and Bashkir environment, not finding an exit to the big science of the big state. Two historical traditions developed separately from one another, without connection with each other. And the need in this regard has been brewing more and more, and is especially relevant today. The peoples of Russia have received the same political status and need to create a single history compiled using the written sources of all peoples.

This very difficult process, in which many researchers will take part, sometimes with completely opposite historical ambitions, will last for a very long time. But it has already begun.

A breakthrough in this direction occurred in the early 90s of the 20th century, when for the first time in Orenburg and Kazan a Russian translation of the 1680 Seyid Djagfar code written in the Bulgarian Turki in Arabic script was published (1, p. 7-323).

However, this edition was met with restraint and there were good reasons for this, since the original code was confiscated from the Vais Bulgars by the NKVD in 1939 at the time of the fierce struggle against pan-Turkism and the translation of the writing of Muslim peoples into the Cyrillic alphabet (5, p. 5, 6) . Only the Russian translation of the Code with the translation of the ancient Turkic calendar to the dates of the Gregorian calendar has been preserved. And this gives reason to some leading archaeologists and historians of Russia, even without reading the Russian translation of the Code, to consider it a modern fake that arose in the era of perestroika, at the time of the rise of the national consciousness of the peoples of Russia.

However, the author of this review, based on the memoirs of his older generation, well represents another era - the era of the 30s, when Russian Orthodox civilization was wiped off the face of the earth by internationalists. And this gives reason to believe that in the 30s other peoples of Russia could have been subjected to the same persecution, and, first of all, the Bulgarist Tatars, who attached great importance to their Turkic ancestors - the ancient Bulgars, who kept chronicles written in Bulgarian in their midst. Turks in Arabic script. Moreover, the possibility is not ruled out that the far-sighted process of transferring the Muslims of the USSR to the Cyrillic alphabet could be conceived to punish the Bulgarists. It was they who were arrested, seized from them ancient manuscripts written in Arabic script and destroyed, while in the families of ordinary Tatars texts with Arabic script were quietly kept, and no one touched them. This gives reason to believe that in the 1930s there could have been translations into Russian of ancient texts that actually existed, including the code of Jagfar of 1680. And some of them, including the chronicle of Emir Gazi Baraj (1229-1246), which is included in this collection, may be of particular interest precisely in terms of the future merger of Russian and Bulgaro-Tatar historiography. Therefore, the author of this review in a number of articles tries to rehabilitate, one after another, small fragments so far of only one of the annals of the Jagfar code - annals of the 13th century. Emir Gazi Baraj - Gazi Baraj tarihi, comparing them with the Tale of Bygone Years and with the Russian translations of authentic Arabic, Jewish and Byzantine sources known to the author (http//www.zlata lvova.narod.ru).

And here's what's interesting. The Pan-Turkist and Muslim Gazi-Baradj, who proceeded in his writings from the greatest role of the Great Bulgars in the history of Eastern Europe, despite his obvious Russophobia and Judeophobia, reaching at times to mockery of the princes of Kievan Rus and the Khagans of the Khazar Kaganate, sometimes covers the history of both states much more complete than the Tale of Bygone Years and well-known Jewish sources, not belittling, but, on the contrary, in spite of itself, exalting the role of these states and their individual representatives.

And this, in turn, refutes the opinion of some researchers who consider it unacceptable when studying the history of their people to use written sources of representatives of other peoples, religions or confessions that are hostile to it.

A further step forward towards the formation of a unified history of the peoples of Russia using the previously ignored written sources of its peoples could be considered the publication in the year organized by Yu.K. Begunov of the collection "Treasures of the Bulgar people" (9, p. 5-302).

The indisputable adornment of the collection is an article by Academician M.Z. Zakiev "Linguistic features of the Volga Bulgars - the main ethnic root of the Tatars".

However, the rest of the collection produces a double impression. On the one hand, it is joyful to see the keen interest of the authors in new sources on the history of the peoples of Eastern Europe and the desire to introduce them into scientific circulation. The works used not only the 1993 F. G.-Kh. Nurutdinov, the Russian translation of the Jagfar code, but also the translation of the code of the Bulgar chronicles of the 14th - 18th centuries, which he is preparing for publication. Nariman tarihi and much more. The erudition of the authors is enormous and far exceeds my own.

But what I can judge at times not only pleases, but also saddens and even horrifies the complete disregard of the authors for any academic rules.

First of all, this also applies to the article by Ph.D. R.Kh. Bariev "The Ancient and Medieval States of the Bulgars", in which he took on the great (I'm not afraid of big words) mission of reviving the completely forgotten in the Bulgaro-Tatar environment, and in Russian historiography, the completely unknown pre-Mongolian history of the main ancestors of the modern Volga Tatars - the Bulgars.

The history of the Bulgars is recreated by the author according to the Russian translation of 1939. chronicles of the Jagfar collection, mainly one of them - the Bulgar chronicle of the 13th century. Gazi-Baradj tarihi. The revival of the forgotten history of a great people is a great thing. And the main goal of such work should be to be accepted and appreciated in scientific circles in Russia, Ukraine, and Bulgaria.

However, this is largely hindered primarily by the complete absence of footnote apparatus. And this is all the more unacceptable because R.Kh. Bariev uses in the article not only the Russian translation of the Jagfar code, but also other sources, in particular the article by F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov "Bulgars and World Civilization" (6, p. 324-347). From an article by F.G.-H. Nurutdinova and, possibly, from some other sources, R.Kh. Bariev took rather controversial information about the ancient history of the Idel Bulgar state, stretching from the Moscow region to the Yenisei, and about its ruling dynasties - Scythian, Sarmatian, Alanian and Hunnic (9, pp. 93, 94).

The hypothesis about the existence of an ancient powerful civilization among the Bulgars, which formed the basis of many civilizations of the world, is not new, and the author has every right to share it. But in the translation of the Jagfar code of the 1993 edition, these data are not available. And since R.Kh. Bariev, according to him, recreates the history of the Bulgars on the basis of the code of Jagfar, then heavy fire from official science, which will immediately fall on R.Kh. Bariev, after the publication of his article, will touch (and how it will touch!) the Russian translation of the Jagfar code, which has nothing to do with the theory of the world significance of the ancient Bulgarian civilization.

In other cases, R.Kh. Bariev, carried away, instead of retelling the code of Jagfar sets out his own vision of historical events, completely moving away from the text of the Bulgar chronicle, but without informing the reader about it, so that everything written is taken by him as a presentation of the text of the code of Jagfar.

So, for example, when describing the events of the middle of the 9th century. Emir Gazi Baraj in his chronicle, the emir bitterly, but impartially writes about how, under pressure from the Khazars, the Kaganate recreated on the Dnieper by Ugyr Aydar on the site of the Kara-Bulgar Saklan Kaganate split into two parts - the Bashtuy (Kiev) principality, headed by Prince Djir and the Khazar governor As - Khalibom (Dir and Askold of the Tale of Bygone Years) and on Saklan on the left bank of the Dnieper. Both states continued to pay tribute to the Khazars, and the son of Ugyr Aidar, kagan Gabdulla Dzhilki, was forced to go to the Volga, where he founded a Muslim state (1, p. 35, 37, 38).

But in R.Kh. Bariev, it looks somewhat different: Gabdulla Dzhilki himself considered it necessary to transfer the capital of his state to the Volga, and to divide the territory of the Dnieper possessions into two provinces (9, p. 102).

There are inaccuracies in the exposition of the code of Jagfar in other places. So, speaking about the adoption of Judaism by the Khazars, R.Kh. Bariev uses not the data of the chronicles of the Jagfar code, but Jewish documents - the well-known letter of the Khazar king Joseph and the work of Yehud Halevi or some authors who referred to them. However, their retelling is inaccurate. King Joseph and Yehuda Halevi report that Judaism became the state religion of the Khazars under King Bulan (2, p. 76, 77, 93, 94, 132), and R.Kh. Bariev names Tsar Obadya, who ruled later and is known for his religious reforms (9, pp. 100, 101). But the Bulgar chronicle Gazi-Baradj of the code of Jagfar, which R.Kh. Bariev, this also does not correspond. According to Gazi-Baradj, Judaism became the state religion in the Khaganate under Bulan's father and Obadi's grandfather Bardzhil. Obadiah also appears in the chronicle, but is called by a different name - Ben-Amin (1, p. 25, 28, 29; 4, p. 20).

The inaccuracies listed above and, possibly, other inaccuracies in the presentation of the Bulgar chronicles of the Jagfar code are extremely dangerous for the reputation of this source, which has not yet been fully accepted in scientific circles.

However, starting from the time of the exodus of Gabdulla Dzhilka from Bashtu to the Kama and Volga in the mid-60s of the 9th century, R.Kh. Bariev no longer goes beyond the framework of the Jagfar code and is of great interest as a new page in the history of the Volga Bulgaro-Tatars - the descendants of the ancient Bulgars. First used by R.Kh. Bariev, the richest data of the Gazi-Baradj chronicle, which is part of the Code of Jagfar, about the formation of the Great Bulgars on the Volga, represent an invaluable contribution to the history of the pre-Mongolian period of the Volga Bulgaro-Tatars. Of particular interest is the table that concludes the article with the genealogy of the Great Bulgar khans from the Dulo clan starting from Attila (9, p. 126).

In a number of other works of the third author of the collection, Doctor, Academician Yu.K. Begunov used data from another set of Bulgarian chronicles of the 14th-18th centuries. - "Nariman tarihi". According to the author, in the 1930s this code suffered the same fate as the code of Jagfar, and the Russian translation of the code compiled at the same time was preserved in the same family of the last owner and publisher of Jagfar tarihi F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov.

This inspires confidence in the code of Nariman tarikha. However, his translation has not yet been published and it is premature to use it as an undeniable written source. Moreover, some of the cited Yu.K. Begunov, fragments of the annals of the Nariman Tarikha code are doubtful.

This refers to the so-called "Teachings of Svyatoslav", allegedly delivered by him on the eve of his campaign in the Balkans (9, pp. 162-168). According to Yu.K. Begunov's “Instructions” were preserved as part of the “Bersala Tarihi” (“Pereyaslav Chronicle”), which was part of the “Nariman Tarihi” collection. At the same time, in the same article, Yu.K. Begunov says that the “Teachings of Svyatoslav”, written in Cyrillic on ancient tablets in the Agil (Balkan) language, were used by Bek Khaidzhin Musa Baltavarly (Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich) in his poem.

These extremely important, moreover, sensational reports should have been accompanied by serious comments by the author of the articles, which, however, are not. It is also unclear to whom the "Instruction" could be addressed.

According to the text of the Teachings, Svyatoslav looks like a Bulgarin - a Tengrian, well aware of the Bulgar mythology and the history of the Turkic-speaking state formations on the Dnieper that preceded Kievan Rus. And this does not contradict the data of Gazi-Baradj about the family ties of the Kyiv princes and khans of the Great Bulgars and about their origin from the ancient Turkic clan Dulo (3, pp. 154, 155). But with the arrival of Salahbi (Oleg) in Bashta (Kyiv) in 882, the ethnic composition of the army and the social elite of the Kyiv principality changed dramatically. Now it consisted largely not of the Bulgars, but of the Slavs - Novgorodians and Scandinavians. Gazi-Baradj (1, pp. 43-45) and the Tale of Bygone Years also speak of this. In the charters of agreements with the Greeks of the Russian princes, the army swears by the Slavic gods - Perun and Volos (7, p. 25, 35, 39, 52), and the texts of these agreements, according to some sources, were written in the Slavic language (8, p. 118).

The army consisting of Slavs and Scandinavians could not adhere to the pro-Bulgarian orientation, and the Bulgarian nobility that still remained in the principality constituted a strong opposition to the princes, refusing to fight the Great Bulgars and the Bulgars of the left bank of the Dnieper (1, p. 87, 88, etc.). To whom, then, was the "Instruction" addressed?

Damages the reputation of the Bulgar chronicles and their introduction into scientific circulation, and much more. In particular, the mention by Academician Yu.K. Begunov, along with them, and articles by F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov "Bulgars and World Civilization" (!) Which was mentioned above, and a new translation of A.I. Umnov-Denisov, which he called "Prinikanie", which refers to the friendship between the Bulgars and the Rus that began in pre-Scythian times.

It will be possible to refer to "Prinikanie", accepting or not accepting its text, only after the publication of A.I. Umnov-Denisov of his proposed translation with its justification. However, even if the reading of the tablets turns out to be correct, it still seems that they themselves could have been written relatively recently (19th century) by members of some secret pagan sect, which in many respects has already lost ancient knowledge.

And Yu.K. Begunov already now, before the publication of A.I. Umnova-Denisova uses "Prinikanie" as an undeniable written source. And this is completely unacceptable, because the author intersperses his quotes "Prinikaniye" with references to the Bulgarian chronicles.

Comments are superfluous.

Thus, Academician Yu.K. Begunov, with regard to the code of Nariman Tarikha, which has not yet appeared in print, did everything possible for a lasting and long-term rejection of these unique texts in the scientific world!

Another circumstance preventing the acceptance of the Bulgar chronicles in scientific circles is the publication in the collection of academician Yu.K. Begunov articles by B.A. Glashev "Chronicle of Karchi" as a source for the study of the history and ethnogenesis of Karachays and Balkars.

According to B.A. Glashev, in the Karachai family of the Khasanovs, two manuscripts were kept, written in Turkic, presumably Bulgaro-Khazar. One of them, the chronicle of Botai, was written in the Greek alphabet and disappeared after the mysterious death of Magomed Khasanov, who took her to Leningrad. But the Soviet era is not the Middle Ages. Before carrying the chronicle, it could and should have been photographed page by page and kept at least a copy of its text.

The second chronicle of Botai's son Barlyu was translated from the Greek alphabet (?) into Arabic at the beginning of the 15th century. Tolgun Chaushegirov, who continued the chronicle. Then, already in Soviet times, historian Nazir Khasanov partially rewrote it in Cyrillic. N. Khasanov failed to publish the chronicle. But as a historian and a literate person, he should have preserved the Arabic text of the chronicle of the 15th century. Why this was not done is unknown. Then, in 1994, N. Khasanov's book was published in Cherkessk. A B.A. Already in 2005 Glashev published in Nalchik his translation of Nazir Khasanov's three chapters.

However, if the work of B.A. Glashev is intended for historians and philologists, along with his translation, he should have republished the book of N. Khasanov, published in Cherkessk, and take measures to find in the archives of the N. Khasanov family the Arabic text of the chronicle of Tolgun Chaushegirova 15th century. This is necessary for the examination of the material on which the chronicle was written, the nature of the Arabic translation, calligraphy, and much more.

When this huge and painstaking work is done, the Karchi chronicle will be accepted by historians as a unique written source and will take its rightful place among other sources. But until it was done to publish an article about the annals of Karchi in one collection with articles devoted to the collections of the Bulgar annals, it was unacceptable to put them on the same level in terms of reliability.

A few more articles by Yu.K. Begunova and F.K.-Kh. Nurutdinova - "The Legend of the Bulgar Epic of the Emperor Askyp Attila", "Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich - the author of "The Tale of Igor's Campaign", "The Battle of Kulikovo in the Light of the Bulgar Sources: A Reply to Rustam Nabiev" significantly exceed the competence of the reviewer and I will not be able to adequately evaluate them , especially since some Bulgar poems (in Russian translation), which are in the archive of F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov and used by the authors of the articles have not yet been published.

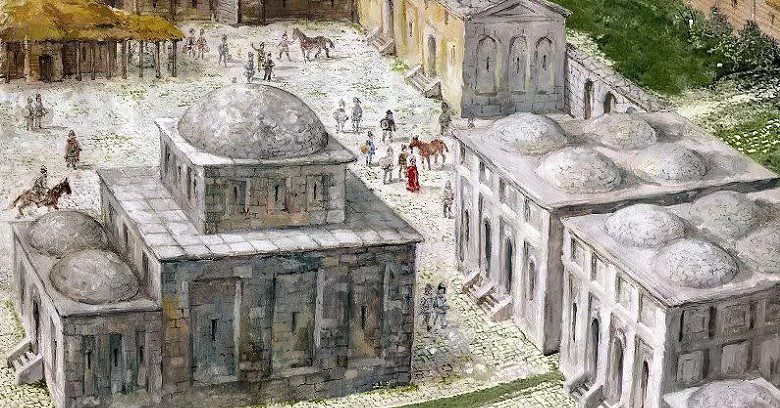

In the final article of the collection, F.G.-H. Nurutdinov "History of the city of Bulgar" should be paid special attention, since it reflects all the difficulties that arise when trying to create a new history of Russia using unique, still unknown written sources.

The author deals with the history of the city of Bulgar and the relationship of the Tatars (Volga Bulgaro-Tatars) with Russia, then with Russia, which included the Kazan Khanate.

However, the introduction of new data into scientific circulation and the extraordinary informativeness of the article are combined with the complete helplessness of its author in compiling a scientific text and with complete disregard for the works on this issue by previous authors, including archaeologists who have been digging the Bulgars for many years - A.P. Smirnova, G.A. Fedorova-Davydova, M.D. Poluboyarinova, who discovered and studied its cultural layers of the 10th - mid-13th century.

In the article by F.G.-H. Nurutdinov uses Russian translations of three Bulgar sources, originally written in Bulgar Türki in Arabic script, but disappeared in 1939 during the campaign to convert Muslims to the Cyrillic alphabet. The translations were kept in the Nigmatullin-Nurutdinov family until 1993, when, as mentioned above, their last owner, F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov managed to publish some of them in Orenburg and Kazan - the collection of Jagfar 1680. Two other sources mentioned by the author are "Chulman tolgau" and a set of annals of the 14th-18th centuries. Nariman tarihy are still kept in the archive of F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov, but should be published in the near future. The use of unknown texts in an article may cause discussion, it will be necessary to check them with the article in which they are mentioned. However, in the text of the article, F.G.-H. Nurutdinov, except for one footnote to these texts, there is not a single footnote to the literature used, or at least an indication of which of the three named sources the author refers to in one place or another. The same applies to the works of Arab writers used in the article - Ibn Fadlan, Al-Muqaddesi, Al-Idrisi, Al-Garnati and others. Some of them were translated by the author himself. But orientalists-Arabists may not agree with him. Therefore, the author would have to refer to the library in which city the manuscripts he mentioned are stored, to the number of their depository, to their inventory numbers, to give a photo of the Arabic text. If these are books, add them to the list of references, make page footnotes.

Another feature of the work of F.G.-H. Nurutdinov is the use of ancient myths along with historical data. According to one of them, Bulgar, the oldest city in the world, was founded around 15000 BC, when a Bulgar Tengrian (?) prayer site was built in its place. And on June 22, 14950 BC. (?!) on this place the first Bulgar empire Idel was proclaimed - "seven tribes".

Sometimes myths reflect the course of distant events, but not in this case. In the era of the Upper Paleolithic, there was still no complex calendar system, and in the Volga-Kama interfluve area, archaeologists have not recorded a vast archaeological culture corresponding to an entire empire.

But there is no distinction between myth and history in the work. Gradually, millennium after millennium, the author comes to the era of Attila, information about which may already be of some interest.

But the fantastic information about the Idel empire cited by the author earlier will cause such rejection and such boundless distrust of both the article and all the sources used in it that after the article is published they will not even be touched for a long time!

Thus, the article by F.G.-H. Nurutdinov in this regard is, as it were, an anti-advertisement to the Bulgarian chronicles that have not yet appeared in print and are probably of considerable interest to historians. This will also affect the already published F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov in 1993 of the Code of Jagfar, which was published only thanks to the heroic labors and efforts of F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov. But… in the same edition with the Bulgar chronicles, under the same cover of F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinov posted his unforgettable article “Bulgars and World Civilization”, which speaks about the world role of the Bulgars since the Ice Age, when they became the first metallurgists (?), that they were involved in the creation of the ancient civilizations of Europe, Asia and America and about many other things (6, pp. 324-347).

Opening the book, the reader first of all gets acquainted with the article of its compiler - with the article by F.G.-Kh. Nurutdinova and slams it shut with anger, without even looking at the texts of the Jagfar code. So the code of Jagfar, barely born for science, was killed by his own publisher. "I gave birth to you, I will kill you..."

And speaking briefly about the articles organized by Yu.K. Begunov of the collection, they contain a great deal of information about the history of the ancient Bulgars, but they do not at all correspond to the academic norms accepted in Russia, and throughout the civilized world. And this will inevitably cause distrust of the new historical sources that the authors use. And I deeply regret this, because the previously unknown Bulgarian chronicles can be of great interest to history.

Literature

1. Bakhshi Iman. Jagfar tarihi. T. I Code of Bulgar Chronicles 1680. / Presentation of the text Jagfar tarihi in Russian, made by a resident of the city of Petropavlovsk I.M.-K. Nigmatullin in 1939. Edition of the bulletin "Bulgaria". Orenburg, 1993.

2. Kokovtsov P.K. Jewish-Khazar correspondence in the X century. L., 1932

3. Lvova Z.A. Some data of the chronicle "Gazi-Baradj Tarihi" about the peoples and states of Eastern Europe in the 9th century. // Archaeological collection, issue 37. St. Petersburg State Publishing House. Hermitage, 2005

4. Lvova Z.A. Who were Tsar Joseph and his ancestors - beks or kagans. // Steppes of Eurasia in the Middle Ages, volume 4, Khazar time. Donetsk, 2005

5. Nurutdinov F.G.-Kh. (I) A few words about the vault. // Bakhshi Iman. Jagfar tarihi. T. I Code of Bulgar Chronicles 1680. / Presentation of the text Jagfar tarihi in Russian, made by a resident of the city of Petropavlovsk I.M.-K. Nigmatullin in 1939. Edition of the bulletin "Bulgaria". Orenburg, 1993

6. Nurutdinov F.G.-Kh. (II) Bulgars and world civilization. // Bakhshi Iman. Jagfar tarihi. T. I Code of Bulgar Chronicles 1680. / Presentation of the text Jagfar tarihi in Russian, made by a resident of the city of Petropavlovsk I.M.-K. Nigmatullin in 1939. Edition of the bulletin "Bulgaria". Orenburg, 1993

7. The Tale of Bygone Years. Text and translation. 4.1. Preparation of the text by D.S. Likhachev and B.A. Romanova. Ed. V.P. Adrianov-Peretz. M.-L., 1950

8. The Tale of Bygone Years. Text and translation. 4.2. Articles and comments by D.S. Likhachev. Ed. V.P. Adrianov-Peretz. M.-L., 1950

9. Treasures of the Bulgar people. Issue 1. Ethnogenesis. History. Culture. Under the editorship of Academician Yu.K. Begunova. St. Petersburg